In addition to picture cards in the strict sense, the collection includes materials similar to picture cards in terms of technique and function, such as matchboxes, poster stamps, paper money, menus, pocket calendars and albums published by companies to host the picture card series or created by collectors as a pastime. At present, around 2,500 items are on display in the museum, while the remainder are conserved inside the archive which can be consulted by scholars on appointment.

The collection can be visited whenever there is an exhibition.

Consult the exhibition programme to view the updated opening hours.

The permanent exhibition on the top floor of Palazzo Santa Margherita presents around 2,500 items, including picture cards, albums, cigarette cards and much more besides.Alongside the permanent exhibition, a display case hosts temporary exhibitions focusing on specific topics: these exhibitions enable the public to get to know portions of the museum’s assets, consisting of around 500,000 items, a few at a time. Below are the most important collections housed in the museum.

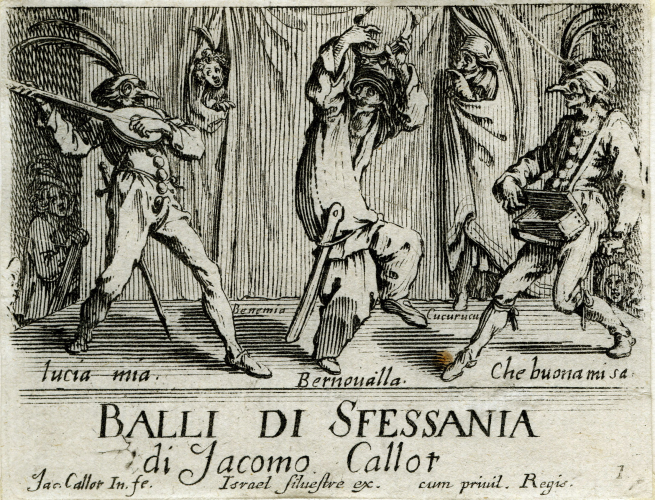

The precursors of trading cards

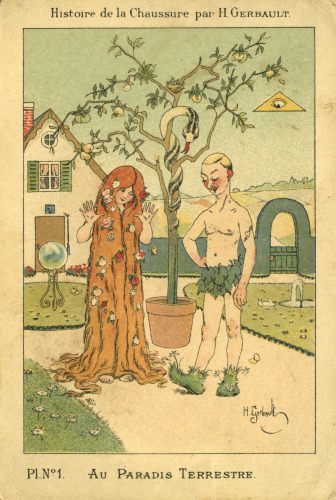

Despite the innovation and specificity of their advertising function and a pronounced secularity, trading cards have some features that could already be found in previous printed materials, by which they were also iconographically influenced. The similarity with some type of older prints is documented by various materials preserved in the so-called “Old Collection”, comprising period engravings and original moulds.Belonging to the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, these materials possess some of the characteristics found later on in trading cards, such as the title, legends, small format and above all division of the themes into sets or sequences of numbered images.The prints became progressively more secular over the centuries, leaving behind their original function as religious precepts. And so the picture card universe developed into an “encyclopaedia” ironizing, chronicling and above all circulating knowledge.

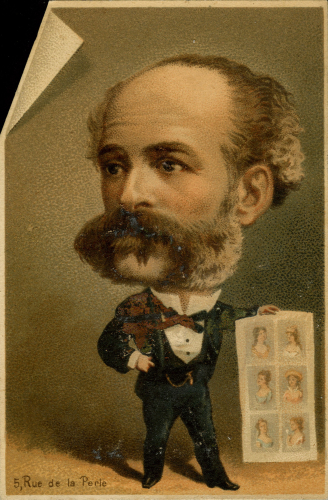

Chromolithography stones

The birth of the picture card and the dissemination of images in the second half of the nineteenth century were the upshot of a print method which would revolutionize the world of graphic art: chromolithography, officially patented in Paris in 1837 by Godefroy Engelmann (1778–1839) and based on the use of a Kehlheim or Solenhofen stone. Although polychrome prints were already possible either using different coloured moulds or watercolours to colour the prints by hand, chromolithography enabled the production of a large quantity of images at a low cost. Furthermore, compared to previous techniques, chromolithography enabled a more extensive colour range and a hitherto unimaginable accuracy of detail. The chromolithographic technique developed from lithography, invented in Munich in 1798 by Aloys Senefelder (1771-1834) and initially used to reproduce music scores. The museum houses several chromolithography stones used as moulds for picture cards.

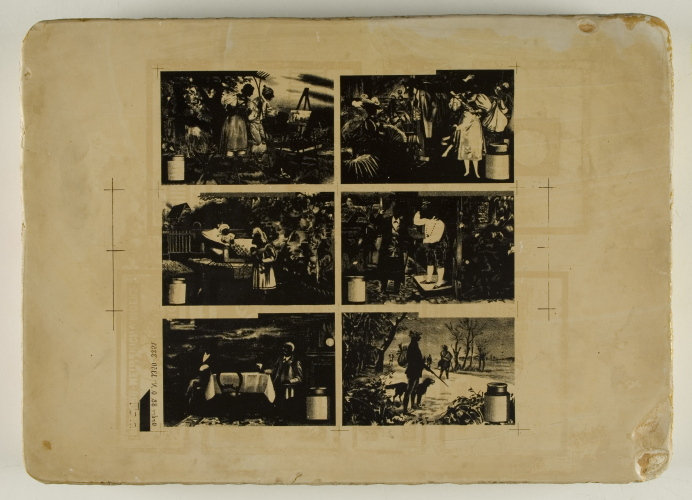

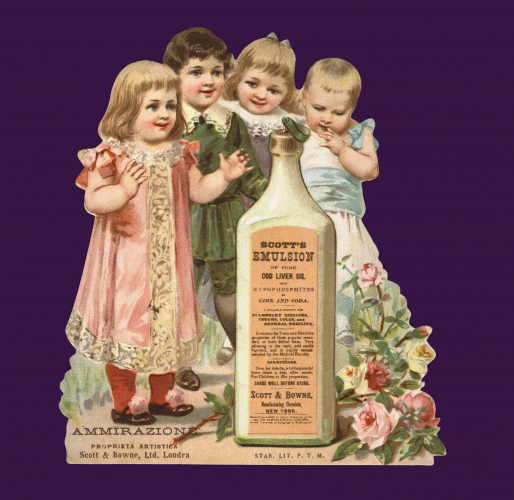

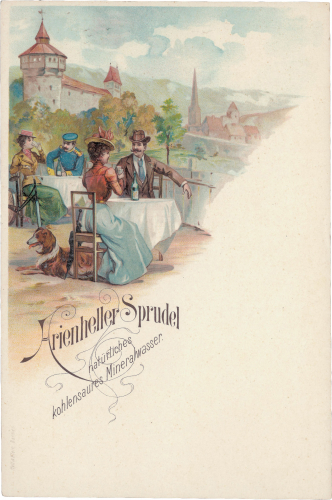

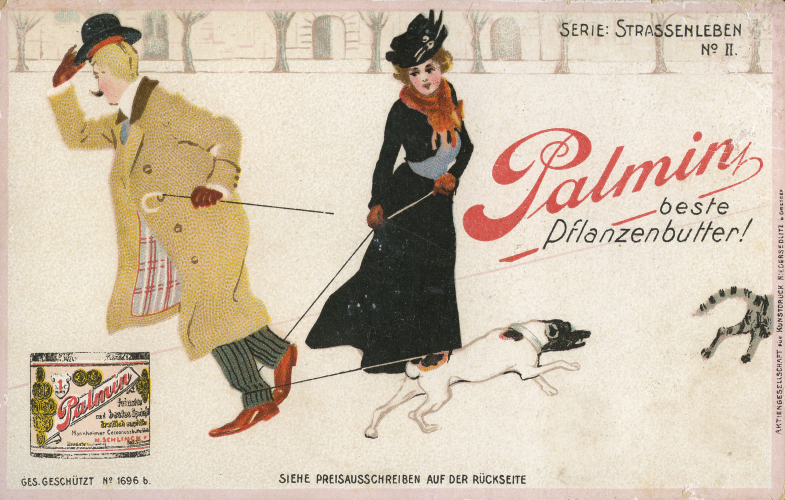

The first trade cards and their spread

In all likelihood, the first trade cards appeared in France in the second half of the nineteenth century, but they quickly spread throughout Europe and the United States thanks to the fortuitous encounter between chromolithography and the need for advertisements spawned by the Industrial Revolution. Consisting of small colour prints with an advertising slogan, nineteenth-century trade cards were different in many ways from the current trading cards. Generally produced in sets of six or twelve on the same theme, the cards were given out in shops and department stores to encourage customers to come back. The formula proved such a sales hit that very soon many lithographic printing works started to print images especially for the purpose, at times leaving blank spaces within scrolls, posters, sails and so on, to make for a more artistic message. A figure who used the picture cards in a winning way was Aristide Boucicaut, founder of the first big department store Bon Marché in Paris in 1852, made famous in 1833 by Zola’s novel Au Bonheur des Dames (The Ladies’ Paradise). After France, other countries also started to print trade cards: the most famous include those linked to Swiss and German chocolate companies, such as Suchard and Stollwerk, and the Italian prize competitions, such as Perugina-Buitoni’s “The Fierce Saladin”.

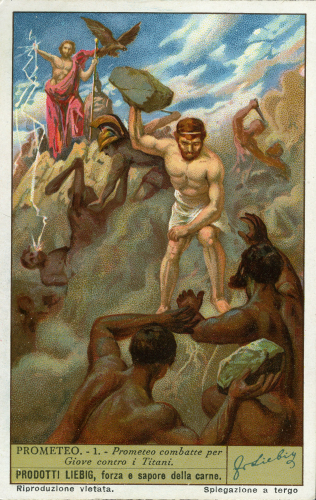

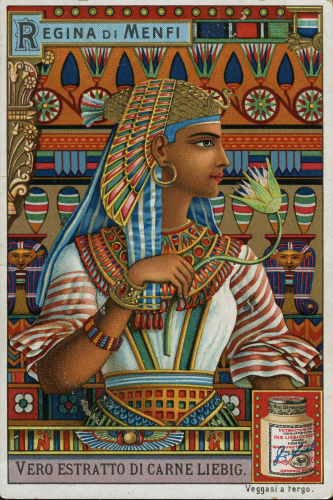

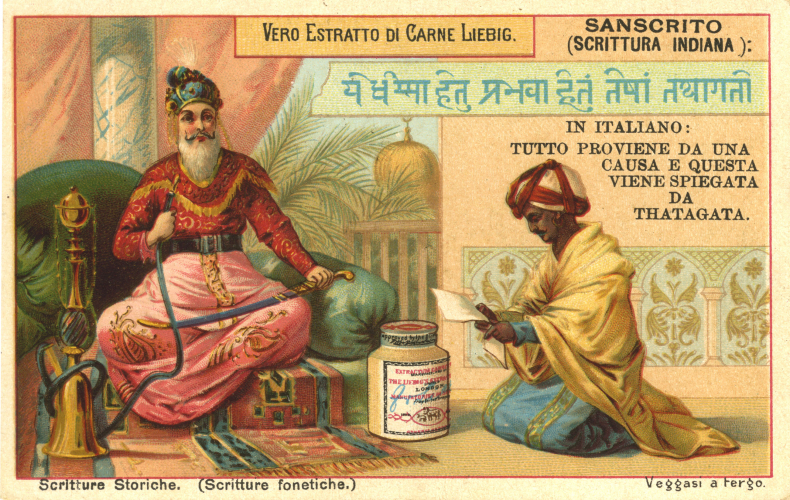

Liebig

The Liebig collection deserves a paragraph of its own. The museum possesses over 44,000 Liebig trade cards: without doubt, the history of trade cards would not have been the same without the essential contribution of the company which linked its name to the printed cards more than any other.Initially distributed now and then, on an irregular basis, and afterwards on a points system, picture cards became the company’s main advertising vehicle. It produced 1,871 sets between 1874 and 1975.The beauty of the images made the cards a universal success: indeed, they were published in French, German, Italian, Flemish, English, Spanish, Dutch, Swedish, Danish, Bohemian and Hungarian. The company did not only produce trade cards, but an enormous quantity of gadgets and printed objects, such as menus, place markers, coasters, calendars and so on and so forth. The formula of the famous concentrated extract of meat was published in 1847 after several years of study, but legend has it that it was discovered by Justus von Liebig after a night spent in his lab in search of a cure for the friend of his daughter struck down with typhus.To get an idea of how famous Liebig products were, just think that when Stanley went on his travels to Africa in search of Livingstone, he took a jar of Liebig’s with him; in 1954 the climbers of K2 did the same; even Jules Verne had the characters of his book Around the Moon drink some tasty cups of Liebig broth.

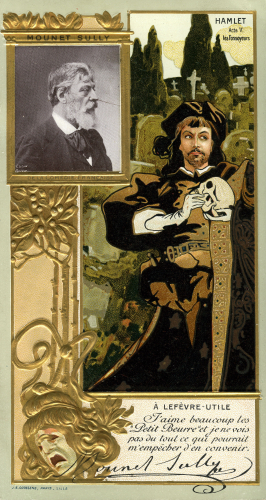

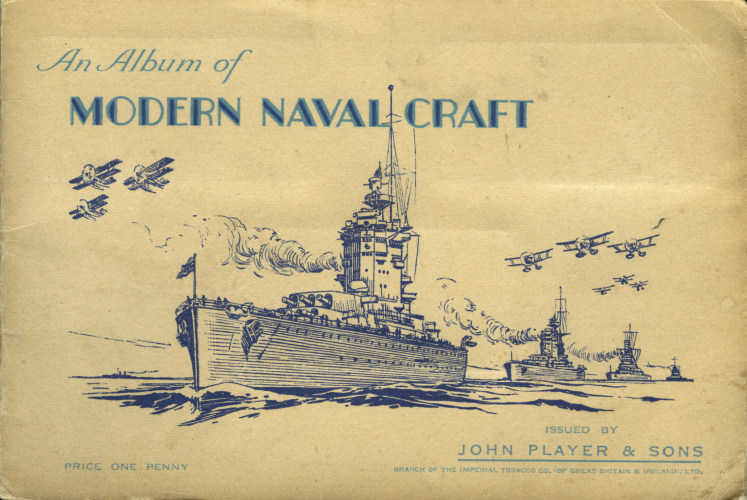

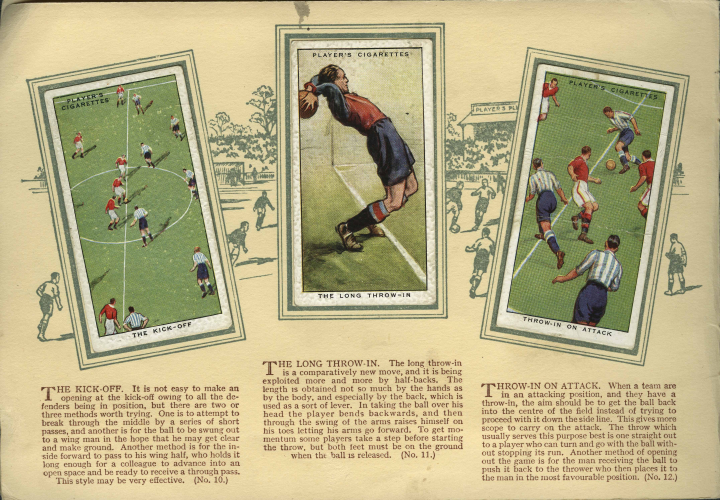

Trade & cigarette cards

Cigarette cards are a particular type of picture card that originated in the United States, around the 1870s. They came about from the practical need to reinforce cigarette packets with cardboard so they would not get squashed if put in a pocket.At first, they were printed with simple reproductions of the company emblem, but then the industries realized that if they printed colour images on the cards, it made the product more appealing and sales increased.Not only that, it also helped to consolidate a certain segment of clientele who periodically bought the same brand of cigarettes just to collect the cards. This type of cigarette card is found in two different formats owing to the different size of packet for 10 or 20 cigarettes.These standards became so recognizable that they were also used to advertise different products such as soaps, tea, starch and much more besides, in this case, taking the name of “trade cards”.

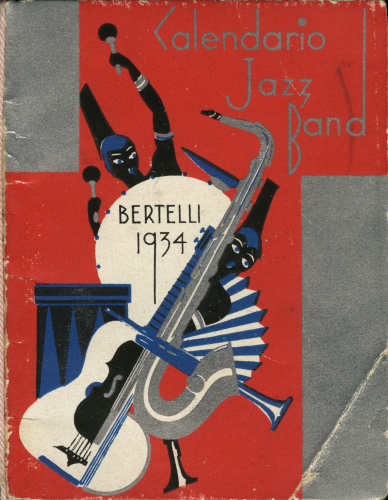

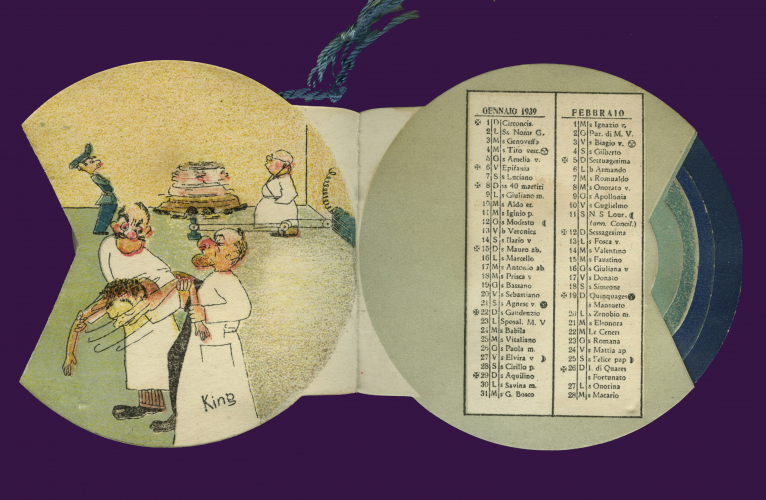

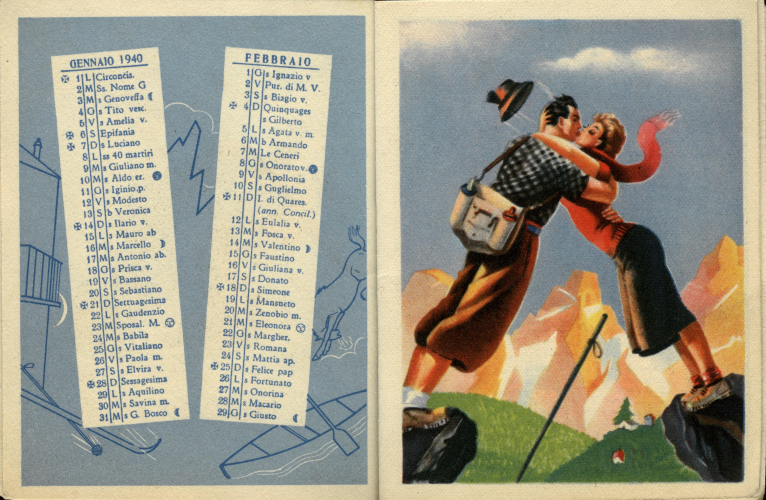

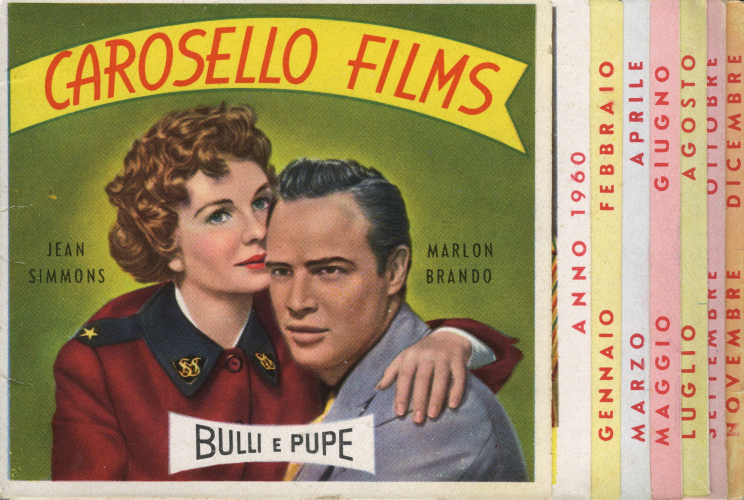

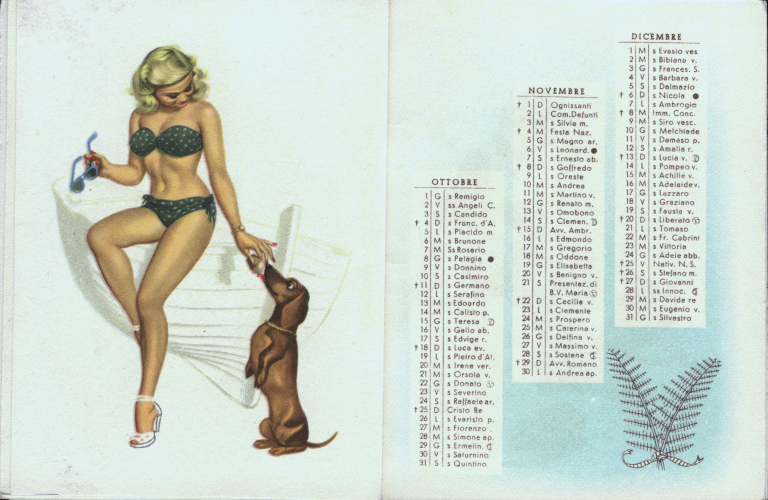

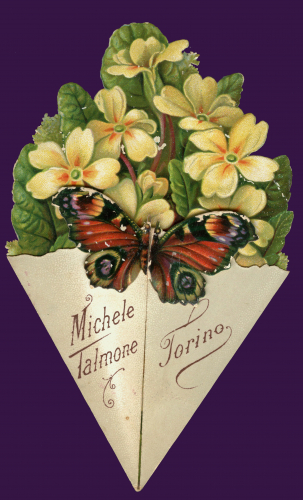

Pocket calendars

The pocket calendars, of which the museum has over 1,000 examples, were given by barbers to their customers to wish them all the best, but also to get a tip in return. Furthermore, the “gift” was not an end unto itself, as it worked perfectly as an advertising gadget thanks to the space reserved for the company name which was a useful memo for customers. These little almanacs were drenched in fragrance and used as a means for advertising perfumes, cosmetics and soaps. Between the 1860s and 1880s initially distributed in department stores, perfume stores and hairdressers, they rapidly became the exclusive domain of barber’s shops. Like mini wall calendars with the months, days, saints’ days and holidays, the pocket calendars were often adorned with captivating images and useful news, and these documents are also a precious source for the history of graphics since they were frequently designed and signed by famous artists.

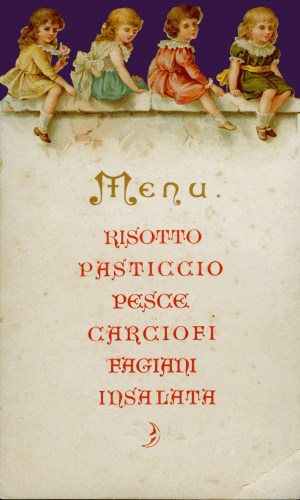

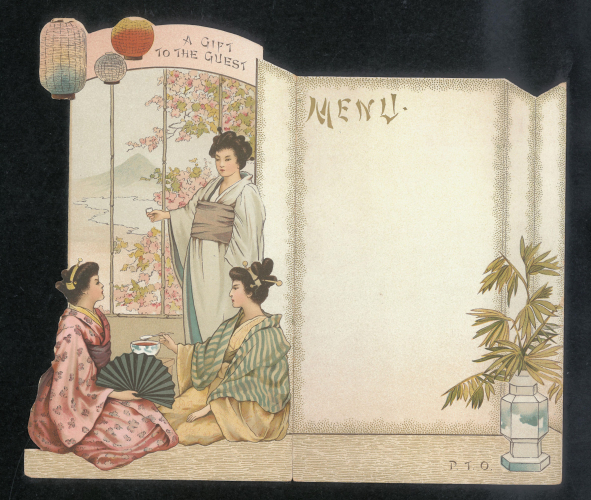

Menus

In general, menus are rectangular pieces of card, but they can also have other shapes, like a book: it had to contain the courses and side dishes in the order of serving, the wines, the place and the date.Several copies of the menu were printed and made available to the diners who could keep them as a souvenir of the occasion. Menus became popular in France and reached their height in quality during the Belle Epoque, also because of the revolutionary capacity of the advent of chromolithography. Owing to their advertising potential, the menus could be offered to a whole range of companies or businesses such as restaurants, shops or champagne, liquor, drink and chocolate producers, and often they came out in numbered sets. Advertising menus continued to be popular at least until the end of the Second World War, before disappearing with the advance of more sophisticated forms of promotion.

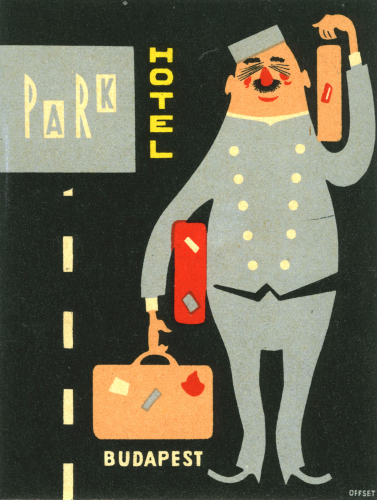

Hotel labels

The Gambini-Ruggiero hotel label collection, comprising around 7,500 items, is divided geographically into 14 folders: the first two are dedicated to Italy followed by Andorra, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, England, Finland, France, Germany, Gibraltar, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Yugoslavia, Africa and Asia, America and Australia. Hotel labels came about with the utilitarian function of preventing travel chests getting mixed up or identifying the station or port of arrival.But as of the 1870s, the labels to glue to luggage became one of the main means of advertising for hotels. At the same time, the middle classes saw them as the most simple and eloquent way of self-proclamation. No longer did they need heraldic symbols and coats of arms, but modern labels with appealing graphics, witness to their globetrotting and economic potential.

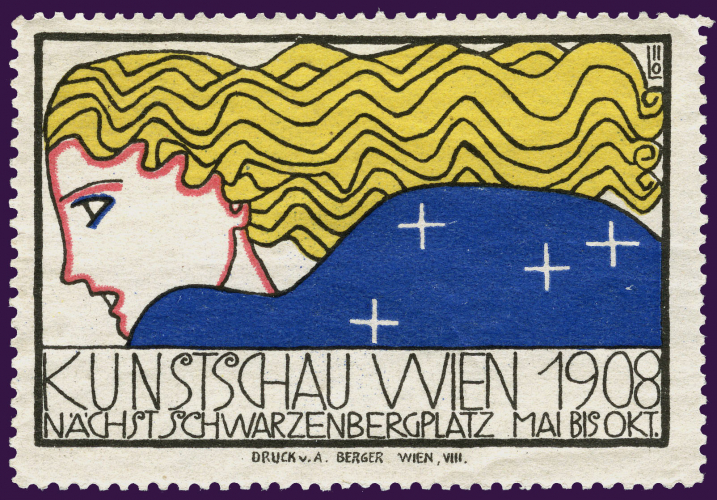

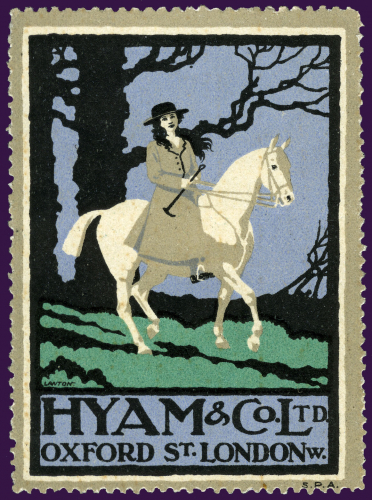

Poster stamps

Among the materials housed in the museum is the second-most important collection of poster stamps in the world – totalling around 65,000 pieces – part of which is the Gambini-Ruggiero collection dating from the end of the nineteenth century to the start of the 1970s. Obsolete for at least 50 years, poster stamps were produced with the aim of advertising a product, a public event, for political propaganda or to commemorate an event.They were given out for free, even though in time some were sold for charity.In this case, they had a face value, because they were used for the public to support situations of dire need: for example, raising money for the victims of the earthquake in Messina and Reggio Calabria (Aid for Sicily and Calabria c. 1909), war orphans, the war wounded, political refugees. In all cases, they were used to seal envelopes or just to decorate them. It can be said that, by function, poster stamps descended from the wax seals used to seal letters before envelopes came into existence, and by form, from postage stamps.

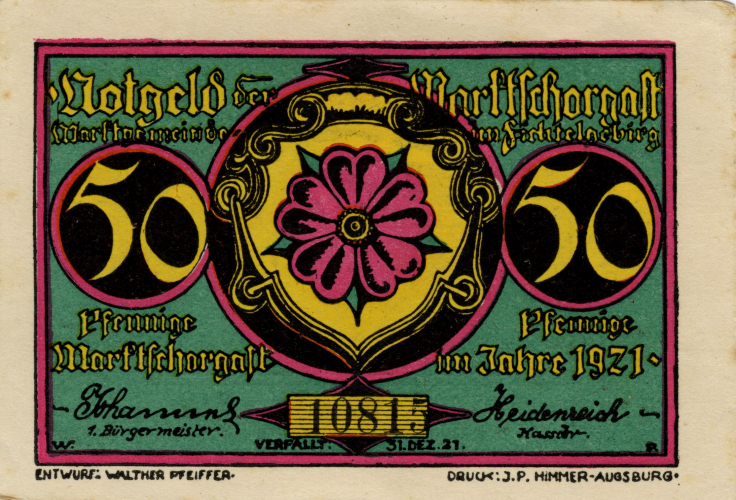

Notgeld

Despite having similar characteristics to picture cards, that is, they were richly illustrated, published in series and small in size, Notgeld nevertheless cannot be likened to them as it was not given out as a gadget and did not have advertising functions.The German term refers to the “emergency bank notes” used in several countries, in particular Germany and Austria, to deal with situations of particular economic difficulty.They were most widespread in moments of monetary difficulty, such as the two World Wars and the early years of the Weimar Republic.Various city councils, associations, banks and private companies already started to issue them around 1914 to make up for the disappearance of coins, taken out of circulation and put away by the population because of the tiny percentages of gold or silver they contained.They were almost always for values less than the mark and the corona, they were not legal tender, but they were accepted as means of payment.

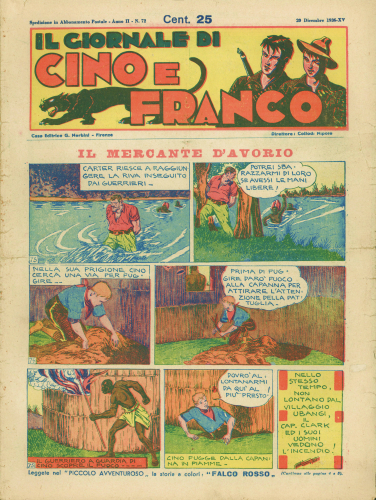

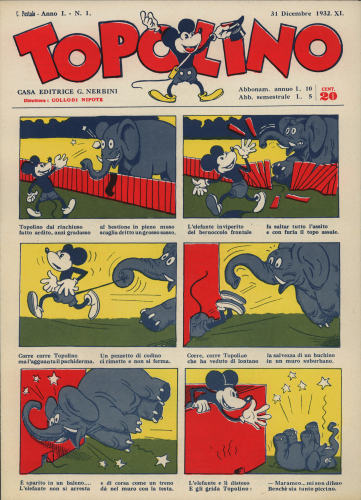

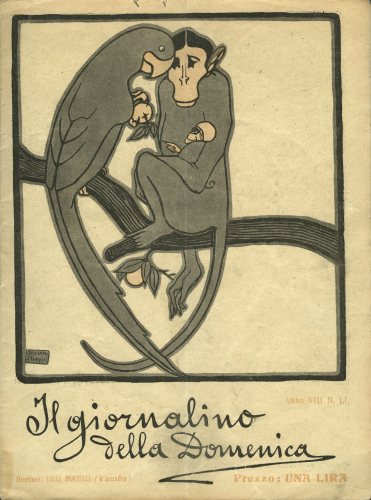

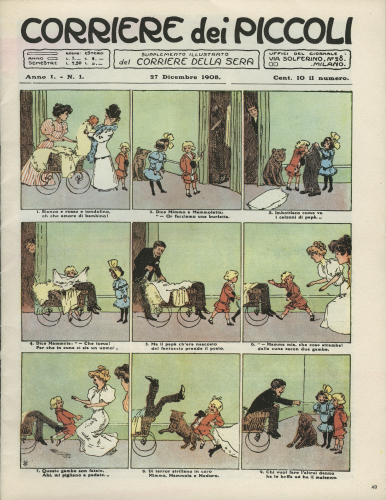

Children’s magazines

The museum’s various collections include the large collection of children’s magazines donated in 1999 by Ruggero Tagliavini and Anna Maria Roccatagliati from Modena.Comprising 851 Italian periodicals from 1812 to the 1950s, the collection significantly documents part of the history of children’s publishing. The most prominent titles include “Topolino” (in Italy the first Mickey Mouse cartoon appeared in 1930 in “Illustrazione del Popolo”) and the “Corrierino”, the longest-lasting of all children’s printed periodicals. A particular mention goes to the magazines aimed at a public of young girls, with columns and advice on gardening, cooking, embroidery, household economics, in order to educate perfect hostesses, upright mothers and devoted wives, which continued until the 1950s. After this decade, traditional children’s magazines went into decline owing to the emergence of photonovels and the advent of television.It is worth underlining that from the outset to the 1950s around 300 magazines came out: a surprising phenomenon if we consider the state of illiteracy and poverty in Italy.

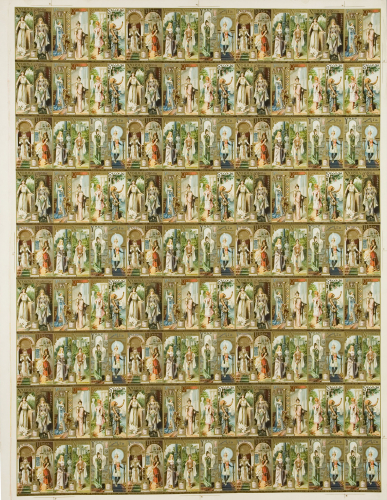

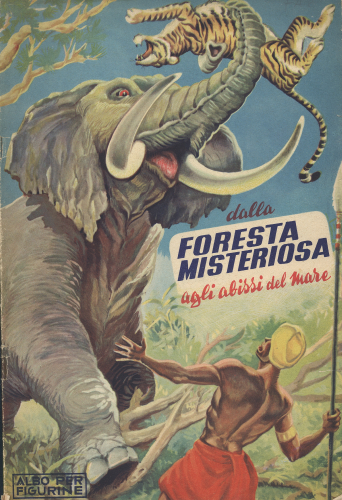

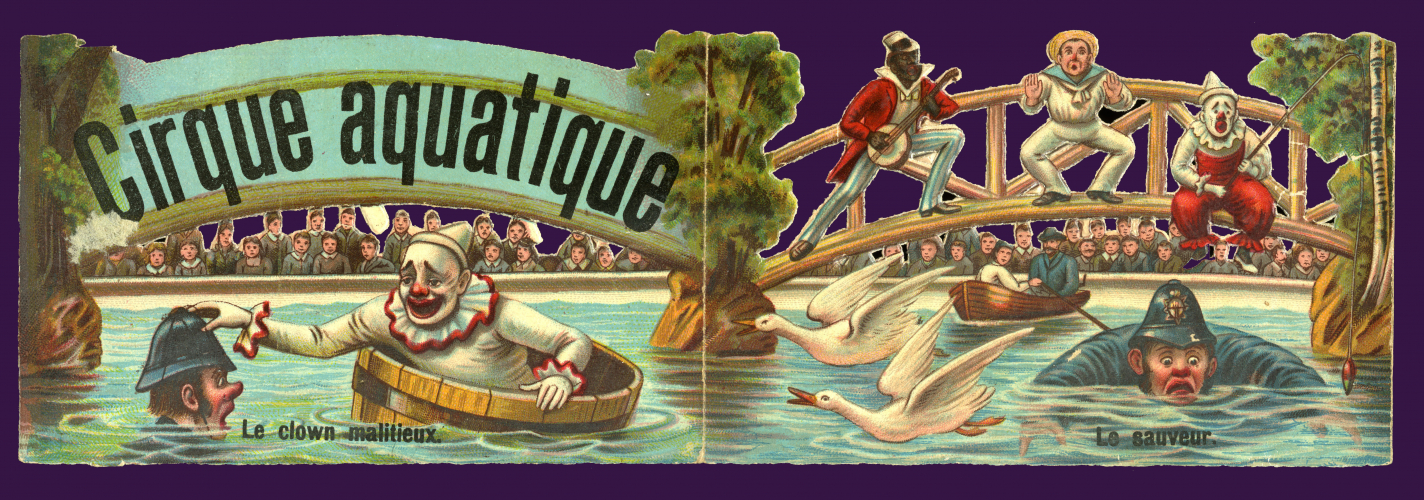

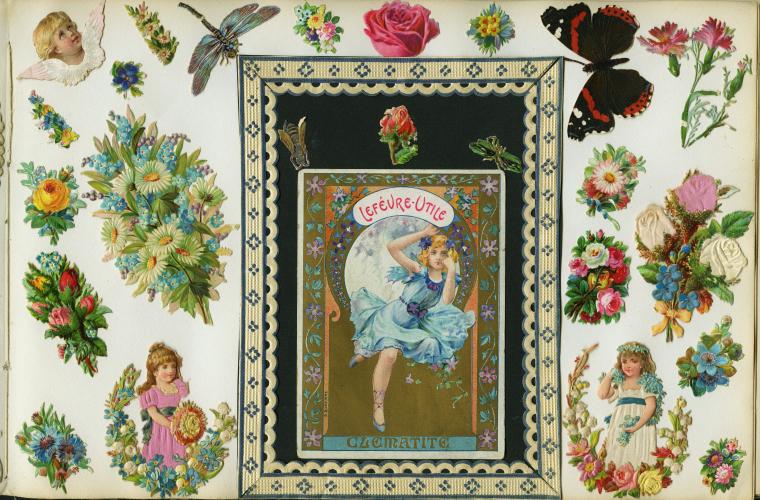

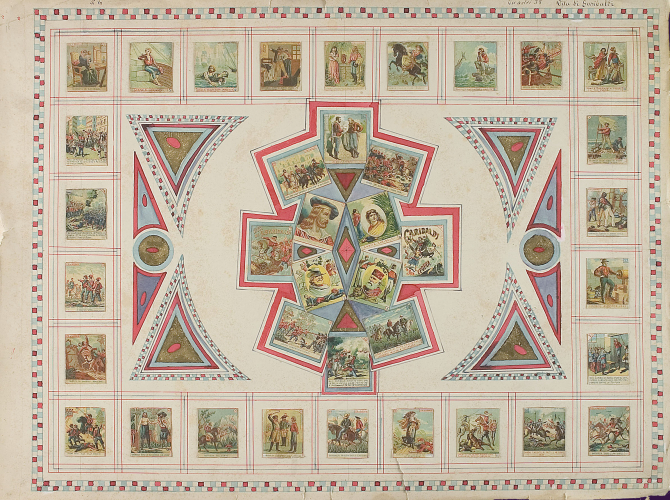

Die-cut prints

The nineteenth-century passion and fascination for colour images can be seen in scrapbooks where they were collected and kept.They were books in which collectors put together a whole assortment of printed papers, in particular trade cards and matchboxes, creating pages according to their own aesthetic taste, decorating them with frames or various kinds of borders, and using anything that was considered worthy of being handed down.They anticipated what would become a requirement: to publish albums to collect trade cards sets. Another particular characteristic frequently found among scrapbookers was the tendency not just to cut up books, but also to cut around the figures printed on loose, rectangular leaves.The only reason for this choice can be aesthetic, that is, preferring shaped images over more or less standardized squares and other forms.All this takes us to a special type of picture card that reflected the taste for rounded or irregular shapes: die-cut prints that were also often embossed, that is, with reliefs.

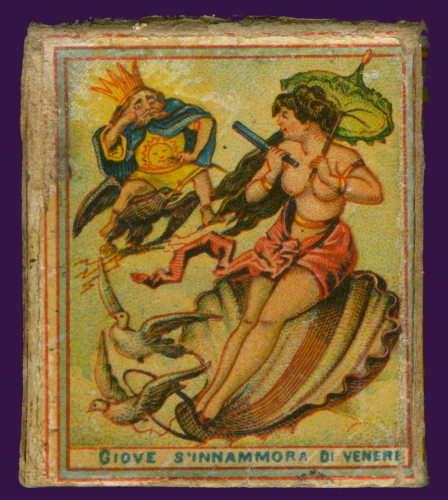

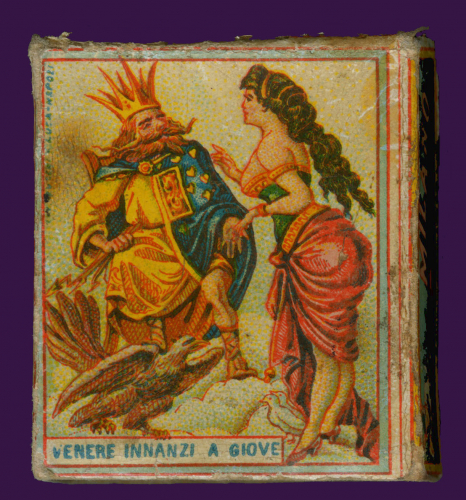

Matchboxes and cigar bands

The images on matchboxes on one hand provided a veritable chronicle of contemporary events and on the other were a sort of encyclopaedia that catalogued the world; they had the task of both educating children and adults and giving an ironic and critical vision of society, somehow taking the place of newspapers and pamphlets.The little images that were often cut out and glued into scrapbooks were also used as furnishings by housewives who sewed them together to make lampshades, table mats, floor mats, fireguards and screens. Among the illustrated materials linked to smoking, cigar bands can boast noble origins, no less.Indeed it seems that behind the invention of cigar bands was none other than Catherine II the Great, tsarina of Russia and passionate smoker, in the attempt to avoid the unpleasant yellowish tinge left on her fingers by the burning tobacco.Instead, according to other sources, the initiator of the new fashion of putting a band around cigars was Gustavo Bock, a European tradesman who moved to Cuba. His reason was to protect smokers’ fingers but also to strengthen the wrapper leaf that keeps the cigar together and mark his products with a sort of brand.Cigar band collecting is given the name of “vitolphilia”.

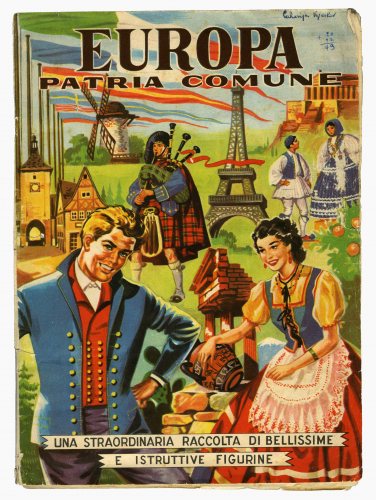

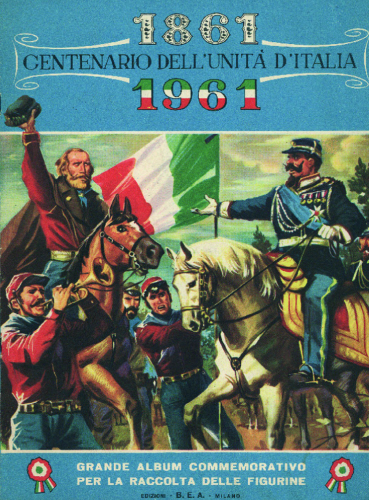

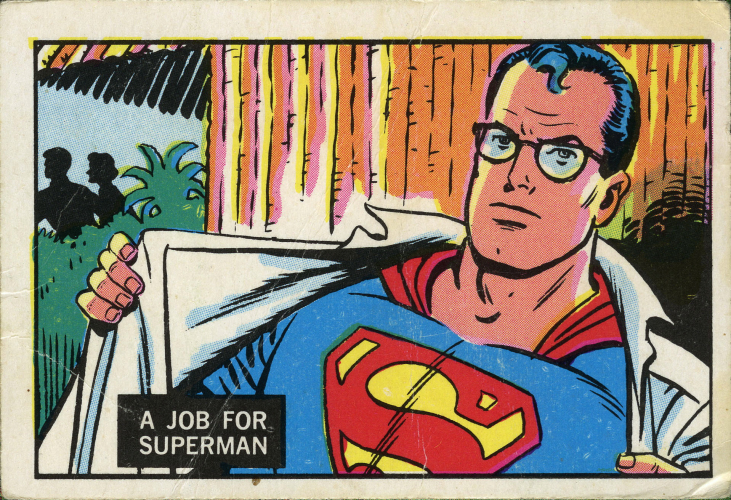

Modern trading cards

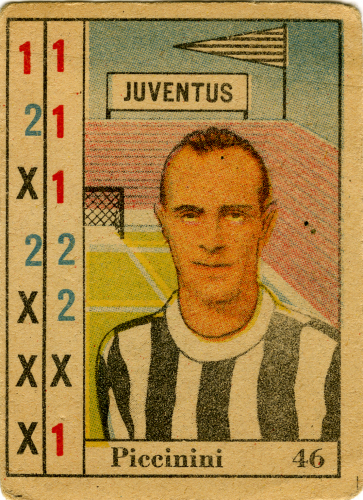

The 1950s were considered the golden age of albums, which started to be sold at newsstands together with the trading cards. They came in sizeable sets with detailed legends. The rebirth of picture cards happened at the end of the 1940s, after the crisis due to chronic paper shortages and problems to get by during and after the Second World War (there was nothing left to advertise). The postwar sporting feats of Coppi and Bartali in cycling and the legendary Turin football team provided the drive for small but active publishers to let their creativity loose and try out new formulas, in just a few years making trading cards a standalone publishing item, free from ties with other products.The main production companies included Nannina, Lampo, Casa editoriale Vecchi and B.E.A; despite the birth of these “purist” publishers, in the 1950s trade cards very much continued to exist, such as the famous cards advertising Lavazza. At the beginning of the 1960s, there was still a good number of trade card publishers.

Panini trading cards

Giuseppe Panini and the newspaper distribution agency run with his brothers in Modena came into contact with the Nannina publishers in Milan. Then, at the end of 1960, Panini bought the unsold trading cards from the “Giant Goal Album” set, the large-size version of the mini-format collection of the same name.He put them in packs, along with a balloon. Sales soared, which encouraged him to do several reprints.At the start of the 1961-62 football season, Panini started to create its first collection of brand trading cards entitled “Footballers”. Hand-produced, this album already contained the ingredients that would make it a publishing sensation over the following years.This was the start of Edizioni Panini of Modena. The repeated success of 1962-63 supplied the conditions to set up a real company: the four brothers Giuseppe, Umberto, Benito and Franco Cosimo Panini soon got together, each bringing his own specialization to the business. In 1965, the back flip of Juventus player Carlo Parola made its first appearance on the album cover, to become a constant fixture on the pack. The original photo was then rehashed by Modenese artist Wainer Vaccari. 1970 was the year when everything started.Two versions were made of Mexico 70, the collection dedicated to the Football World Championship: one produced exclusively for the Italian market, the other the first Panini collection devised for the international market, with multilingual texts and legends in English, French and German.A publishing formula was created that made minimum adaptations for the local versions, while safeguarding the central body of the album and above all the trading cards.They could circulate freely in any country, with obvious advantages for their distribution.From now on, the magic of trading card packs would expand to the whole world. Shortly afterwards, sister companies were set up all over Europe, in the United States (the cards were then sold in candy and hot dog kiosks, the only channels similar to European newsstands) and in Canada.In other countries, distribution was in the hands of local dealers who were strictly controlled by the Modenese parent company, the manufacturing centre, right from the creation of the images to the packaging.

Donations

The Museo della Figurina would not exist without the donation of Giuseppe Panini, without doubt one of Italy’s greatest collectors.He was not just passionate about trading cards, but also photographs and postcards, books, magazines and puzzle books, and accordions. Also thanks to the continual, generous donations of collectors and enthusiasts, the museum has been able to carry on increasing its collections in time.The donated materials, housed in the museum archive, and visible in part in the permanent display, are put on view in periodical themed exhibitions.

List of donors:

- Mario De Filippis

- Antonio Mascolo

- Ruggero Tagliavini e Anna Maria Roccatagliati

- Donazione Roveri

- Francesco, Antonio, Anna Maria e Tiziana Panini

- Museo Civico di Modena

- Annalisa Malavolta

- Franco Diotallevi

- Franco Dominianni

- Grani & Partners

- Miroslav Benassi

- Nadia Lodi Detlef Lorenz

- Anna Toscano

- Jorge Henrique

- Giovanni Spagnuolo

- Carlo Olivieri

- Bruna Toselli e Giuseppe Vincenzi

- Angelo Sola

- Dino Motta

- Vittorio Pranzini

- Luciano Quartara

- Eliana Farotto

- Paola ed Enrico Zanotto

- Mauro Zanichelli

- Horst Machalz

- Mario Bianchi

- Carlo Bellucci

- Mauro e Gianpietro Salomoni

- Orlando Nelson Pacheco Acuña

- Angela Lorenz

- Gisella Barberini

- Donazione Tabili e Santoloni

- Manuel Vaccari

- Gianni Valbonesi

- Paolo Santini

- Federico Meda

- Fol-Bo, Rastignano (BO)

- Federica Graziosi

- Il salotto del libro di Taglio di Po

- Maurizio Puviani

- Maria Malpighi

- Franco Chiarini

- Carmela Deidda

- Luciano Marrucci

- Antonia Rubichi

- Maurizio De Paoli

- Piera Martinelli

- Moreno Moretti